The Story of Pilvax

Wandering around Pilvax Alley in the city centre, I can’t stop thinking about what happened to the meeting point of the revolutionary youth - one of the most well-known cafés in Budapest.

Several buildings used to stand on Pilvax Alley and one of them hosted the Pilvax Café. The Pilvax’s building, as well as Sándor Petőfi’s last home called Marczibányi House, was in a wrong place for the large scale construction works taking place in the 20th century . Therefore, the Marczibányi House was replaced by the Guttman House on the corner of Rákóczi street and Síp street, while the Pilvax was knocked down. That’s the reason the Pilvax Café is not in its original place. In spite of the fact that the building was honoured with a memorial tablet in 1900, it was completely gone by 1911.

The legendary Pilvax Café is the heir of Café Renessaince on the former Úri street (today: PetőfI Sándor street). Café Renessaince was founded by Ferenc Privorsky in 1838, and Károly Pilvax was his bartender. Pilvax was an austrian young man who moved to Budapest, married a Hungarian woman, and took over the café in 1841. His wife insisted on having their name on the name-board, so they renamed the place “Pilvax”.

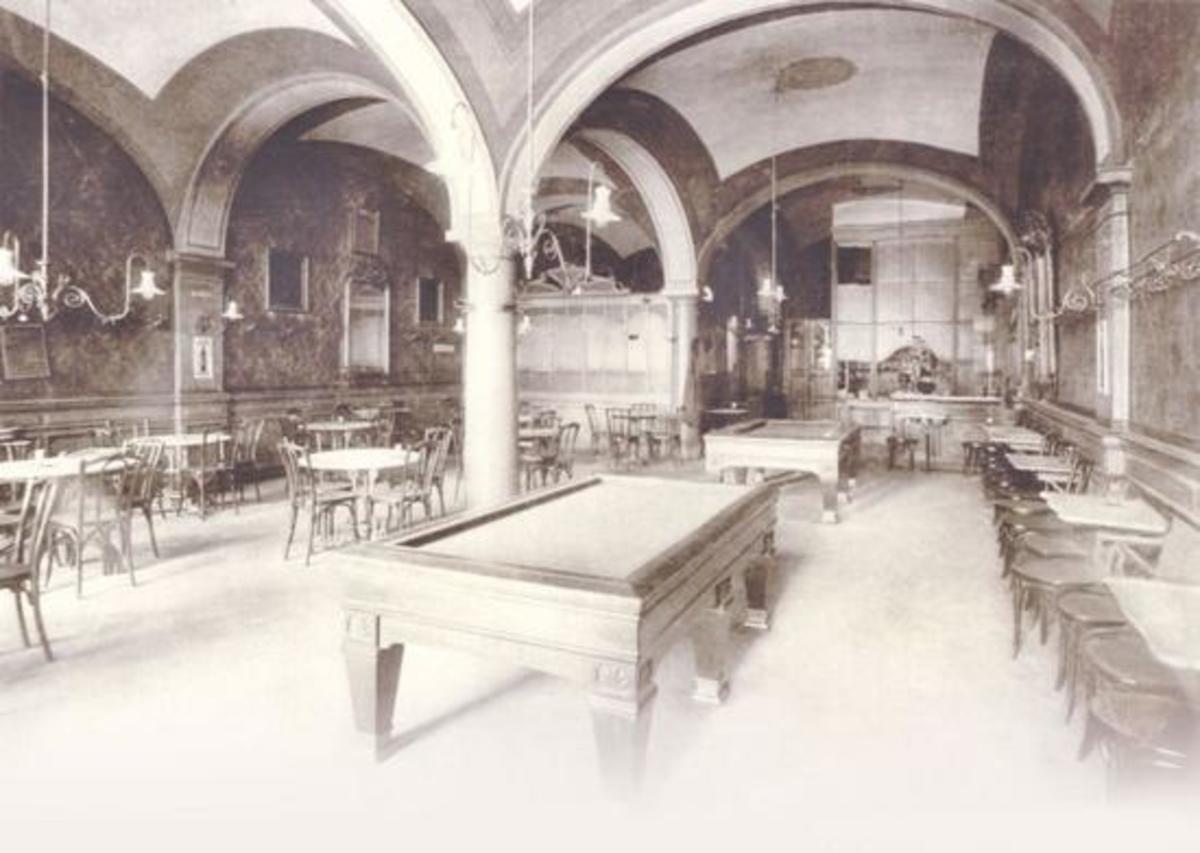

What was the Pilvax like? People went there to play pool, cards, read newspapers, eat out, and socialize. During the Hungarian Reform Era (between 1825 and 1848) Buda and Pest had more than 40 cafés. These places also functioned as networking centres. The owners had the newest papers, traders met here to exchange news, and university students (at the time: only men) met here. Cafés were ideal for dates, too.

Károly Pilvax rented the café to János Fillinger in 1846, who didn’t change its name. In 1846, Pilvax was an iconic meeting point for the youth. Famous figures of The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 like Mór Jókai, Sándor Petőfi, and Mihály Tompa started to round up here.

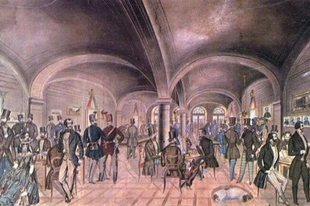

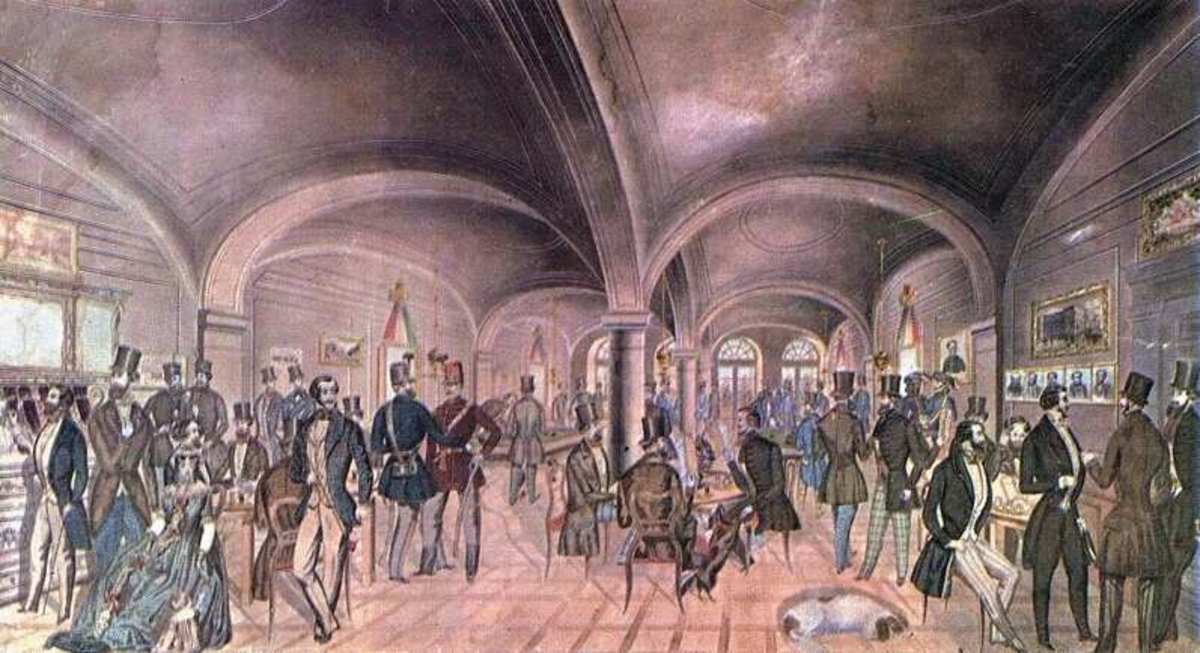

Pilvax looked like this during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

Pilvax looked like this during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

The intellectuals and the radical-minded had their meetings at Pilvax Café. Following the footsteps of Lajos Kossuth, on 11th March 1848 the young József Irinyi wrote the demands of the revolution in 12 points here. The revolutionary youth wanted to get these 12 points to the parliament in Bratislava (in Hungarian: Pozsony) to support the reformist opposition.

On the night of 14th March a man from Bratislava brought the news that the revolution broke out in Vienna. Next day Sándor Petőfi recited the National Song. Pilvax Café was renamed to “Hall of Freedom”. The café became the centre of the revolution, it was used even as a recruiting office during the fight for freedom.

After several of the revolutionary youth got killed and the fight for freedom failed, the café was renamed Café Herrengasse, and was run by a new leaseholder.

The old Pilvax before its demolishion. Source: Sulinet

The old Pilvax before its demolishion. Source: Sulinet

At the end of the 19h century, Pilvax had a huge competition due to the unification of Pest and Buda into a metropolis. Other cafés became the centre of cultural life. Finally, the building was demolished in 1911, and the Pilvax disappeared.

In 1921 another Pilvax was founded on Városház street, which is still open.

The New Pilvax in Budapest

Source: Fortepan

Source: Fortepan

The Story of Hotel Britannia

Walking down the Grand Boulevard from Oktogon to Nyugati Railway Station the most exciting sight is the former Hotel Britannia, which is one of the few hotels that survived the historical storms and could function as a hotel and café since 1913. After its opening, the whole hotel got central heating, hot and cold running water, which was extraordinary at the time.

Hotel Britannia was among the high-end hotels of Budapest, and the kitchen was run by a famous chef. Britannia was the first restaurant in Budapest to fulfill needs of customers who were on a diet. The successor of Britannia Hotel is Radisson Blu Beke Hotel, maintaining this good habit: they serve wheat-free, lactose-free and sugar-free meals and desserts, too.

Best years of Britannia were in the 1930s, when the Nyugat Circle had its meetings at the hotel. They rented a separate room for the occasion, and the events had a high value in the current cultural life.

On New Year’s Eve of 1930 Zsigmond Móricz, the well-known writer held a party at Britannia, joined by 120 co-workers at Nyugat, and their friends and family. The event was so grandiose, the greatest figures of the 1930s literature didn’t stop partying till 5am.

This photo was taken on New Year’s Eve in 1938 in the ballroom. The walls were decorated with Jenő Haranghy’s enormous panel paintings depicting famous Shakespeare dramas like Measure for Measure, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer’s Night Dream, The Merchant of Venice, Twelfth Night, or What You Will, ect.

Aladár Németh, the current manager of the hotel found a market niche, and decided to build an elegant ballroom able to seat hundreds of people, as at that time there were no such places in Budapest.

Poets and writers of Nyugat at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music

Poets and writers of Nyugat at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music

But life at Britannia didn’t stop after New Year’s Eve. On Mondays, psychologists gave presentations at the hotel. Tuesdays were dedicated for poets, Wednesdays were ruled by novelists. On these days, Britannia was filled with the words of the era’s greatest minds like Mihály Babits, Frigyes Karinthy, Dezső Kosztolányi, Gyula Illyés, or Lőrincz Szabó. Thursdays were hosted by Endre Nagy. On Fridays, fine arts were in focus with artists like Pál Pátzay, Róbert Berény (whose lost paintings were in the set of Stuart Little), Oszkár Glatz or Károly Kernstock. Saturdays were women’s nights with Ilona Kernách, Frigyes Karinthy, Gréte Harsányi, János Kodolányi, and Vilma Medgyaszay.

Even a record was broken on the summer of 1931: Endre Nagy facilitated arguments on 108 presentations and events within a few months.

Ferenc Móra, the famous writer was also a regular visitor at Britannia. He called the hotel his second home. He usually stayed in the same room, which is today called the “Móra room”, decorated with the writer’s portrait and 12 original Móra-quotes.

The Story of Centrál

If you are eager to breathe into the living history, and have some spare time at Ferencziek Square, Centrál Café is the way to go. The famous café was founded in 1887, and quickly became a cultural hotspot at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

Central Café functioned as a cultural incubator, where the progressive minds of the early 20th century could meet and network. The café was predestined to be an intellectual centre, as the building was surrounded by cultural institutions, editorial offices, publishing agencies, the ELTE unversity library and the Metropolitan Library. A Hét (The Week)’s editorial staff held their meetings here, which gave an opportunity for the youth of The Week to found a new paper called Nyugat (West), where all the greatest minds of the era had the chance to publish their thoughts. Nyugat had its weekly meetings on Wednesday at Centrál, attended by people like Endre Ady, Dezső Kosztolányi, Frigyes Karinthy, Mihály Babits or Ferenc Molnár.

Between 1930 and 1940 female writers started their meetings at Centrál, too, and founded the Kaffka Margit Association.

The building was owned by Ullmann Lajos Erényi, and the interior was designed by Zsigmond Quittner. The café was on the ground floor of the building, consisting of eight rooms, two playrooms, a kitchen and a cloakroom. The design could be described as historicizing eclectics: the rooms were furnished with thonet chairs, marvel tables with cast-iron legs, persian carpets, plush sofas, with city photos and mirrors on the walls.

Which is your favourite historic cafe? Let me know in the comments, and I might drop a visit there, too!